By Karen Kidd, PM

(I speak only for me)

If you’re planning to show up in Georgia wearing a tank top, short-shorts, and flip flops, better keep it to Stone Mountain Park, Hearse Ghost Tours, Jimmy Carter National Historic Site and other such places. The Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Georgia, the largest male-only Freemasonic obedience in the state, is having none of it.

“No Mason shall attend any Meeting wearing shorts, an uncollared shirt, t-shirt, exercise wear, open-toed shoes, sandals, or flip flops unless medically necessary,” Grand Lodge of Georgia Grand Master Michael H. Wilson said in his edict issued late last month.

Nothing herein shall be construed as prohibiting a Brother from wearing jeans or overalls with a collared shirt or any required medical device. Nothing herein shall be construed as requiring a Brother to wear a suit, sport coat, tie, or tuxedo unless the Worshipful Master so directs.

The first thing that caught my attention was the notion that medical situations exist that require the wearing of flip flops (apparently it isn’t just a post-mani-ped thing). Once I got over that, it occurred to me just how damning it is that a Grand Master anywhere has to tell Freemasons how to dress in Lodge; that enough Brethren there don’t already know.

And if they don’t already know that . . . well, it’s yet another sign that we’re doomed.

Granted, the Georgia edict inevitably would puzzle a Freemason, such as myself, hailing from an Order where everyone wears pretty much the same thing in lodge (guys wear white suits, gals wear white robes, it’s all very standardized).

Granted, the Georgia edict inevitably would puzzle a Freemason, such as myself, hailing from an Order where everyone wears pretty much the same thing in lodge (guys wear white suits, gals wear white robes, it’s all very standardized).

Something like the Georgia edict just wouldn’t come up in the Order to which I belong. It just wouldn’t. The Brethren in that Order already know, they don’t have to be told. That said . . .

I think Georgia’s back story also is relevant as the Grand Lodge of Georgia has long been an outlier in Freemasonry.

In 2009, a Lodge under that obedience filed suit in DeKalb County Superior Court after the Grand Master of Georgia decreed a Masonic trial would be conducted to hear complaints about the lodge’s decision to enter a Brother of color.

That same year, in a more hushed up controversy, the Grand Lodge of Georgia pressured the allegedly independent Order of Eastern Star (OES) to expel its Co-Masonic members or lose the right to meeting in premises owned by Freemasons under the male-only body in that state. The Georgia OES dutifully ferreted out and expelled those members found to be Co-Masons, including one sister who had been a member of the OES for 25 years.

In September 2015, then Grand Lodge of Georgia Grand Master Douglas W. McDonald issued an edict that outlawed homosexuals among its membership.

The following year, then Grand Lodge of California Grand Master M. David Perry declared Georgia’s outlawing of Homosexuality to be “a sectarian stand which is inconsistent with and does not support the General Regulations of Freemasonry.” With that, the Grand Lodge of California withdrew recognition from Georgia and the Grand Lodge of Tennessee, which had issued its own similar edicts and other paper. The Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia likewise withdrew recognition from the grand lodges in Georgia and Tennessee.

McDonald resigned entirely from the fraternity earlier this year “for religious reasons” and that particular unpleasantness seems to have settled down.

I bring all that up to point out that a dress code edict is a very mild edict to come out of Georgia.

Chris Hodapp, in his always delightful and informative “Freemasons for Dummies” blog, argues that this edict points up a debate between “Exterior” Freemasons and “Interior” Freemasons. The Exterior brethren apparently feel that attire not fit for a visit with the Queen, attending a Nobel Prize event, or a five-star restaurant is an affront to the Craft; while Interior brothers opine that it’s what’s in a Freemason’s heart that counts and are just fine being clothed for Lodge as if they’re going to Denny’s.

It makes me wonder how far the latter group is from advocating showing up sky clad for lodge meetings, but that would be a very distracting digression. Maybe another blog.

Per usual, I can see a middle ground between the two extremes and how the latest edict out of Georgia might be trying to find it; but I also see something deeper going on here. It seems both extremes have forgotten more than a little history; and what they should already know without being told.

Historically, dress in a Lodge of Freemasons wasn’t all about showing respect to the Craft (who gets along just fine, regardless of how we dress). It’s supposed to be about recognizing how we meet, act and part with everyone but most especially with our brethren.

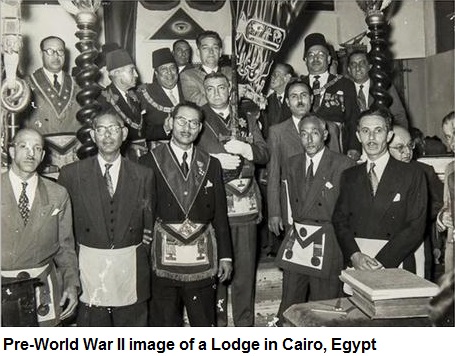

In the beginning, dressing for Lodge meant attire just a little less fit for a monarch’s court. It wasn’t a specific dress code or requirement so much as that’s how folks in the propertied upper classes, the group most attracted to Freemasonry during that period, dressed when they were out in public. It would be disrespectful to others to dress otherwise.

In the beginning, dressing for Lodge meant attire just a little less fit for a monarch’s court. It wasn’t a specific dress code or requirement so much as that’s how folks in the propertied upper classes, the group most attracted to Freemasonry during that period, dressed when they were out in public. It would be disrespectful to others to dress otherwise.

Likewise, dressing up for lodge wasn’t about dressing well or showing respect to the Craft so much as it was about being the equal of every Brother in the Lodge. With everyone dressed more or less the same, it’s difficult to identify someone’s social rank, especially in a dimly lit room.

One piece of Masonic garb that once was de rigueur, but now isn’t so much in the U.S., are the white cotton gloves. The idea behind them in Freemasonry was/is that two Brothers shaking hands could not determine each other’s profession based on the roughness, or lack thereof, of their hands.

It wasn’t about the gloves, it was how the Brothers viewed each other: as equals.

As the decades wore on, Lodge attire continued to track what its members wore in public, where even hobos wore a suit jacket and a hat – always a hat. However, though folks generally wore much the same thing – and not a tank top in sight – it still remained obvious who everyone was in life, based on their clothing. If you were going someplace very special, you still expressed it by wearing your best, even if it basically was a grander version of what you wore all the time.

As the decades wore on, Lodge attire continued to track what its members wore in public, where even hobos wore a suit jacket and a hat – always a hat. However, though folks generally wore much the same thing – and not a tank top in sight – it still remained obvious who everyone was in life, based on their clothing. If you were going someplace very special, you still expressed it by wearing your best, even if it basically was a grander version of what you wore all the time.

On that level, it could seem only natural that Lodge attire would track clothing fashion trends outside the Lodge, where things started getting very casual in the late 1960s. That view would ignore the very important exceptions to those casual trends that everyone recognized and still recognizes.

Even in our very casual age, folks still know when they should dress up and when they don’t need to. Folks don’t have to be told that they must dress up when they attend a wedding or go someplace else they consider very special. They don’t need to be told that, they just know.

Apparently in Georgia, enough of the brethren need to be told that the Lodge is a very special place that an edict is necessary.

I imagine those same brothers do know to dress up for their friend’s wedding but they are just fine with wearing PT shorts, a club T-shirt, and tube socks to Lodge. Because they don’t know the Lodge is very special to them.

If they don’t know that, then what else don’t they know?

Civilization is slipping and there are many signs of that. This is one of them.

Excellent article thats spells out cornerstones of the foundation on which Freemasonry stands.

LikeLike

“Folks don’t have to be told that they must dress up when they attend a wedding or go someplace else they consider very special. They don’t need to be told that, they just know…”

Don’t you believe it for a second.

LikeLike

Well, maybe not in the crowd YOU run with (snicker) :-p~~~~~

LikeLike

“Civilization is slipping and there are many signs of that. This is one of them.”

No, this is a shift in culture, in a very small part of the United States. You’re going to need more examples than Georgia, and more research than assumptions of the content of Georgian character, to show that all of “civilization is slipping”. Clothing itself is a social construct.

LikeLike