By Karen Kidd, PM

(I speak only for me)

Welcome to Part II of blogs about Masonic Scholars and why they do what they do.

Welcome to Part II of blogs about Masonic Scholars and why they do what they do.

In March 1918, Grand Lodge of Iowa Grand Historian Joseph E. Morcombe penned a letter to North American Universal Co-Freemasonry Grand Commander Louis Goaziou about a Brother who had expressed some “facts” to him about Masonic history. “Facts” that were verifiably wrong but to which the other Brother was weirdly attached.

“Yet such as he are the leaders and light-givers of the brethren,” Morcombe wrote. “They will not dig for facts, taking their own intuitions or the mere say-so of others as ignorant as themselves as gospel, against all arguments that can be brought.”

In the same letter, Morcombe also doubted why he bothered to labor as a Masonic historian, surrounded as he was by so many “ignorant” brethren.

“When will American Masons be open-minded and logical; when will they search for the light of truth without stipulating ahead or on the way that they will not venture into certain fields? Sometimes I am disgusted enough with hypocrites and ignorances in the Craft to cease my endeavors. But then comes the new ascension of the fighting spirit, and I try to hit all the harder.”

In my observation, that “fighting spirit,” rather than any attention payed by rank-and-file Freemasons or what very little support or rewards the labor attracts, is what drives the majority of modern scholars in the Craft. Each one must figure out for themselves why they do that thing they do. They must define for themselves how to measure their “success” – or lack thereof – and develop strategies to attain that success.

Masonic scholars who ponder that today are largely building on the work of scholars who came before and who, in their own time, had to do their own pondering.

– James Steakley

I suppose the best place to start is with the fellow who, in my most humble opinion, was the greatest scholar of all time, Albert Pike. 1

Pike’s mortal remains lie where he died, in the House of the Temple of the Scottish Rite’s Southern Jurisdiction in Washington D.C. Pike was a financial failure at almost everything else he tried but he excelled in Ritual development and Masonic research.

Pike also wrote many books, including his “Book of Words” and “Meaning of Masonry”2 but is best known for one of his earliest works, “Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite,” which for decades well into the 20th Century was presented to newly raised Malecraft Masons. Millions of copies sit mostly unread on shelves throughout the world.

No one has more books of Masonic research in print than Albert Pike but how he can be considered a success and what his strategies were is still up for debate. “Success” and “strategy” for the Masonic scholar aren’t defined the same way as it would be in other scholarly fields. For the Masonic scholar, success often is all about getting the work done before dying; and strategy – assuming there one – is figuring out how to achieve the first objective.

Many don’t realize that Pike died on the job, in the House of the Temple, because he could not afford to retire. He depended almost entirely upon the patronage and financial support of the Southern Jurisdiction. Though it was for him very much a labor of love, he also clearly had no choice but to so continue until he died. And he did.

Which brings up a very important observation about achieving success in Masonic research: it won’t make you rich. It will not, in fact, bring you much – if any – financial reward at all, despite the great sacrifice it requires. If you really want to be a “success”, then you’re going to have to find a way to finance it.

Which means, of course – and you know what’s coming – don’t quit your day job.

I know of few Masonic Researchers who actually live by their research or their pen; I know of none who make it entirely on royalties. Those who do manage to devote themselves to full time research are those who enjoy financial backing of some sort. For the majority, being a Masonic researcher means working by day, toiling over their latest project during breaks and stolen moments at work, at night, on weekends and any other time away from their private avocation.

Their loved ones think they’re crazy which, in my opinion, experience and observation, is true. Without the support of family and friends, the Masonic researcher can have no hope of “success”, by any definition.

There have, of course, been Masonic researchers who were wealthy and financed their studies. These include William Preston, the 18th and 19th Century Masonic Lecturer whose name today makes up the first half the Ritual referred to as the “Preston-Webb,” worked in most US Malecraft Lodges today. He achieved success and he had a strategy to do it.

However, Preston and others like him are in the extreme minority of Masonic Scholars. Most relied/rely on the support of others and their own incomes to continue their research.

Jeremy Ladd Cross, the great Ritual developer of the early 19th Century whose “True Masonic Chart” remains a standard, was a hatter by profession. Thomas Smith Webb, the second half of “Preston-Webb”, was a book seller and manufacturer of wall paper. Carl Claudy, the 20th Century author of Masonic history, esoterica and fiction, was a journalist and freelance writer. Albert Mackey, an early compiler and writer of Masonic history, was a high-priced physician.

history.ucla.edu/faculty/margaret-jacob-2

Even scholars of Masonry who are not themselves Freemasons do not live by their books alone. Margaret Jacob, whose work includes “Origins of Freemasonry: Facts and Fiction,” is a highly successful academic who teaches at UCLA. David Stevenson, who has written a great deal about the Craft, including his own “Origins of Freemasonry,” is Emeritus Professor of Scottish History at the University of St Andrews. Jessica Harland-Jacobs, author of “Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927,” is associate professor of history at the University of Florida.

Masonic scholars fortunate enough to be published may receive royalties but they are likely to spend far, far, faaaaaaaar more on research. Their tax preparers, like mine, classify what they do as a “hobby,” that it cannot be claimed – by any stretch – as a living. So far as the IRS is concerned, research does not define who the Masonic scholar is, much as the scholar may beg to differ.

So, all that said, the paramount strategy toward achieving success in Masonic Research, especially as a nonacademic, is to – somehow – find a way to finance it. For most Masonic scholars, that strategy involves “patronage” of some kind.

Patronage, in my experience, is a resource – any resource – that someone else parts with to advance a scholar’s endeavors. There are few Masonic researchers who rely on only one patron. Most, me included, have many patrons.

The greatest form of patronage in Masonic research is other researchers in the field; those willing to mentor, share discoveries and collaborate in the work. Many is the time I’ve been stymied in my research and another scholar – often a scholar who is not a Freemason – has provided me the one piece I couldn’t find on my own.

My greatest mentor, who watches over me from thousands of miles away, whom I seldom meet but who has provided so much in the way of time, material and faith, is Neil Wynes Morse. Morse is one of the world’s leading experts in Masonic ritual development, past president of the Australia and New Zealand Masonic Research Council (ANZMRC) and is known to many in Freemasonry as “the Canberra Curmudgeon”. He mentors many but I like to think I’m his favorite 😀

Of course, all the information in the world won’t get past your keyboard if you can’t keep a roof over your head or pay shipping and handling costs to some otherwise unappreciated librarian six states away for an obscure document s/he just photocopied for you. Sad to say, success in this field often comes down to cold, hard cash and where to get it.

I’ve heard that grants and awards to finance research exist but I’ve never secured one of these. Within Freemasonry, this kind of patronage is usually reserved for malecraft researchers or those scholars of Freemasonry who don’t write anything the malecraft don’t want written. If you are a Freemason in an Obedience not in amity with the 50 largest malecraft grand lodges in the US, and especially if you are a female Freemason, the usual sources of Masonic patronage simply are not available to you.

However, patronage takes many other forms. For me, patronage is a couch to sleep on while I’m in town visiting a local library.

It is a meal, a drink, bus fare or a seat in a car during a research road trip, room and board.

It’s someone willing to visit a dusty old archive on my behalf to look up something they can physically get to but that they may not, themselves, understand.

It’s air miles or some other way to shorten the physical distance between me and some small, cryptic bit of truth I’m after.

It’s not wondering aloud just how insane I might be.

And all I, and any other scholar, can ever do, by way of recompense, is say, “Thank you.”

All of that is patronage.

Patronage also is a kind, listening ear, sympathetic smiles and a great deal of love, attention, encouragement and patience. I want to place especial emphasis on the latter, patience. For as I mentioned earlier, all of us in Masonic research and publishing are crazy. Those who love, encourage and enable us in this madness are so very important for any success – however it is defined – that we may ever have in this field.

Another hurdle for the Masonic scholar is time. I’m not the best manager of that very precious commodity. When I’m in the throes of a project, I can’t sleep for long periods. Any spare moment is suborned to study. I plague my local library with impossible inter-library loan requests that they always manage to pull off.

I become very manic and intense when I catch the scent of something that has long eluded me. In these periods, I can be very hard to be around and quite difficult to get along with. I advise anyone considering or already laboring in the field of Masonic scholarship to do as I say, not as I do: manage well your time.

I also recommend something I like to think I’m a little better at: maintaining a strong back bone and unbreakable integrity – though others call it “stubbornness” and “being unreasonable.” Being the scholar in the room often means being the designated grown up. A good scholar, in any field, is insufferably objective and unable to toe any party line.

This attracts hostility from all sides.

Folks with agendas to push and axes to grind will seek you out and, trust me, they will find you. When they do, you’ll have to keep your mind focused on the truth and stick to it, even when it would be easier to give in to those for whom the truth takes distant second to internal politics or some other goal.

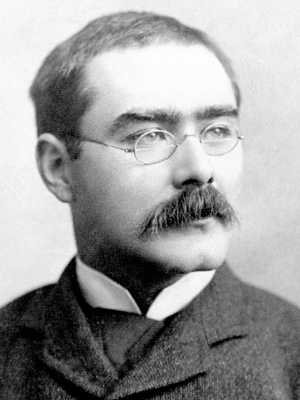

I recommend memorizing the poem “If” by the Freemason Rudyard Kipling; and, if you are a Freemason, paying extra close attention to your lessons in the Third; and if you’re York Rite, the Mark.

The greatest hurdle for a Masonic scholar is to figure out why they do that thing they do. The “why” is something each scholar must answer for themselves and while that answer may not always be the same for one scholar, compared to another, I think I have come upon a general reason “why” we do what we do.

Of course, the Masonic scholar can go a long time without answering that question but cannot count themselves a master until s/he does.

“Why are you doing this?”

“Because you are the only one who can.”

__________________________________

1 Yeah, I know there are folks who will want to debate that point with me. Take a number and, for now and for the sake of this blog, just go with it.

2 You young whipper snappers should appreciate these links. I can remember when it was almost impossible to lay hands on even a hard copy of Pike’s lesser circulated work. Seriously, up hill both ways!